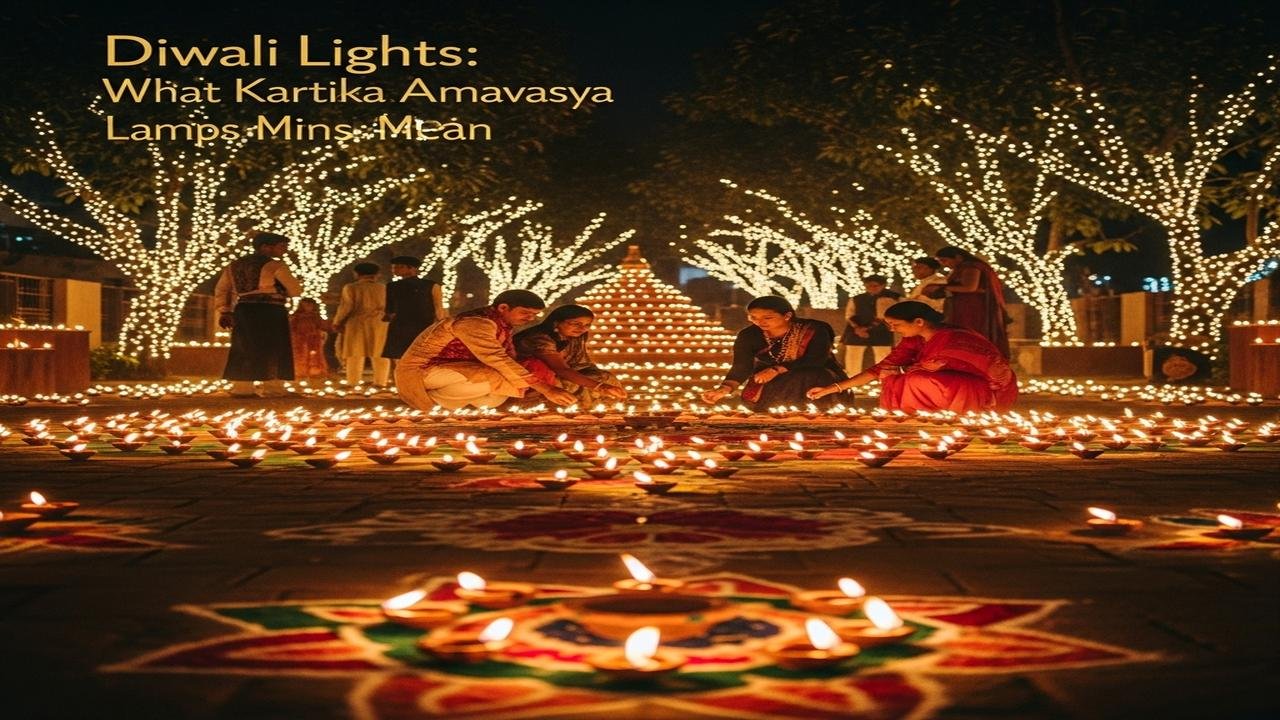

Diwali Lights: What Kartika Amavasya Lamps Mean

Why lights are central to Diwali

Diwali, often called Deepavali — “row of lamps” — is observed on the new‑moon night (Amavasya) of the lunar month of Kartika, usually in October or November. Across India the festival is experienced through household lamps, strings of lights, and public illuminations. Why light? The answer is layered: it is religious, philosophical, social and practical. Different communities foreground different meanings, and those meanings have evolved over centuries.

Calendar and historical outline

Diwali’s core date is the Kartika Amavasya (new‑moon tithi), but the festival is a multi‑day sequence in many regions: Dhanteras (Dhantrayodashi), Naraka Chaturdashi, the main Diwali night, and the following Pratipada which marks new beginnings like the Gujarati new year or Govardhan Puja in some traditions. Medieval puranic literature, temple calendars and local chronicles helped shape the timing and rituals; folk stories, court customs and trade guild practices further layered the meanings.

Three broad religious narratives that explain the lamps

- Rama’s return: In many North Indian retellings of the Ramayana, the people of Ayodhya welcomed Rama, Sita and Lakshmana back after exile by lighting lamps across the city. The lamps signify joy at the restoration of order and the return of righteous rule (dharma — ethical duty).

- Lakshmi and prosperity: For many Vaishnava and Smarta households, the Diwali night is Lakshmi Puja — lamps invite Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and well‑being, to enter homes and marketplaces. Puranic and medieval accounts associate Kartika Amavasya with propitiatory rites for prosperity.

- Kali, Naraka and liberation: In Bengal and parts of eastern India, the new‑moon night is associated with Kali Puja and the goddess’s fierce, radiant power. In South India, the preceding Naraka Chaturdashi commemorates Krishna’s or Shiva’s defeat of demonic forces; lighting marks victory over ignorance and bondage.

These narratives are not mutually exclusive. Regional practice often blends them: the same lamps can signify the homecoming of an epic hero, the welcome to a goddess, and the inner triumph over personal darkness.

Philosophical symbolism: light as inner knowledge

One enduring interpretive thread is symbolic. In many Hindu philosophical and devotional registers, light represents jnana — knowledge — and darkness represents avidya — ignorance. Lighting lamps on Diwali thus becomes a ritual enactment of the aspiration to dispel ethical and spiritual darkness, to renew clarity and purpose. Gītā commentators and other teachers have used light imagery to discuss discrimination (viveka), discernment and illumination of the self, though they place this within differing doctrinal frames.

Social, economic and practical reasons

The practice also has social and practical roots:

- Community visibility: Lamps make streets and houses visible at night, supporting social gathering, worship and commerce.

- Marking cycles: Diwali coincides with the end of the harvest and the closing of business accounts in many trading communities; lighting announces abundance and the start of a new financial year for some guilds.

- Domestic order: The festival follows cleaning, decorating and re‑ordering of homes; illumination completes the ritual of renewal.

How different traditions emphasize the lamp

- Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava and Smārta households: May focus on the philosophical ‘light over darkness’ theme or specific deity pujas (Lakshmi, Rama, Vishnu forms).

- Śākta regions: In parts of Bengal and Assam, the new moon night is Kali Puja; lights are used in a devotional context that foregrounds goddess power rather than domestic prosperity.

- Jain and Sikh commemorations: Jains observe Diwali as the anniversary of Mahavira’s liberation, lighting lamps in temples; Sikhs celebrate Bandi Chhor Divas, remembering the release of Guru Hargobind, marked by illumination at the Golden Temple and gurdwaras. These observances show how the symbolism of light as joy and freedom crosses religious lines.

Ritual forms of lighting

- Earthen lamps (diyas) filled with oil or ghee

- Rowed lamps on windowsills and balconies

- Large temple lamps and public lightings

- Modern electric strings and decorative lighting

Each form carries local meaning: oil lamps link to older agrarian and household practices; electric lights reflect contemporary public display and convenience.

Contemporary concerns and adaptations

While lamps remain central, modern practices raise environmental and safety questions. Fireworks and excessive lighting have prompted public debate about air quality, noise and fire risk. Many communities now encourage simpler lighting, eco‑friendly lamps, LED alternatives, community pujas and quieter celebrations. These adaptations show the festival’s capacity to refigure its meanings in changing social contexts.

Final reflections

Lighting lamps on Diwali is both plain and profound. At one level it is a communal habit shaped by calendars, trade rhythms and seasons. At another it is a living symbol — homecoming, prosperity, victory, and spiritual illumination — whose meanings shift between regions, sects and households. Rather than a single “original” reason, Diwali’s lights are a mosaic of history, scripture, local memory and lived devotion, all making the same night a shared moment of brightness.

Note: Traditional Diwali practices can include fasting or prolonged ritual activity; if you have health concerns, consult a medical professional before adopting such practices.