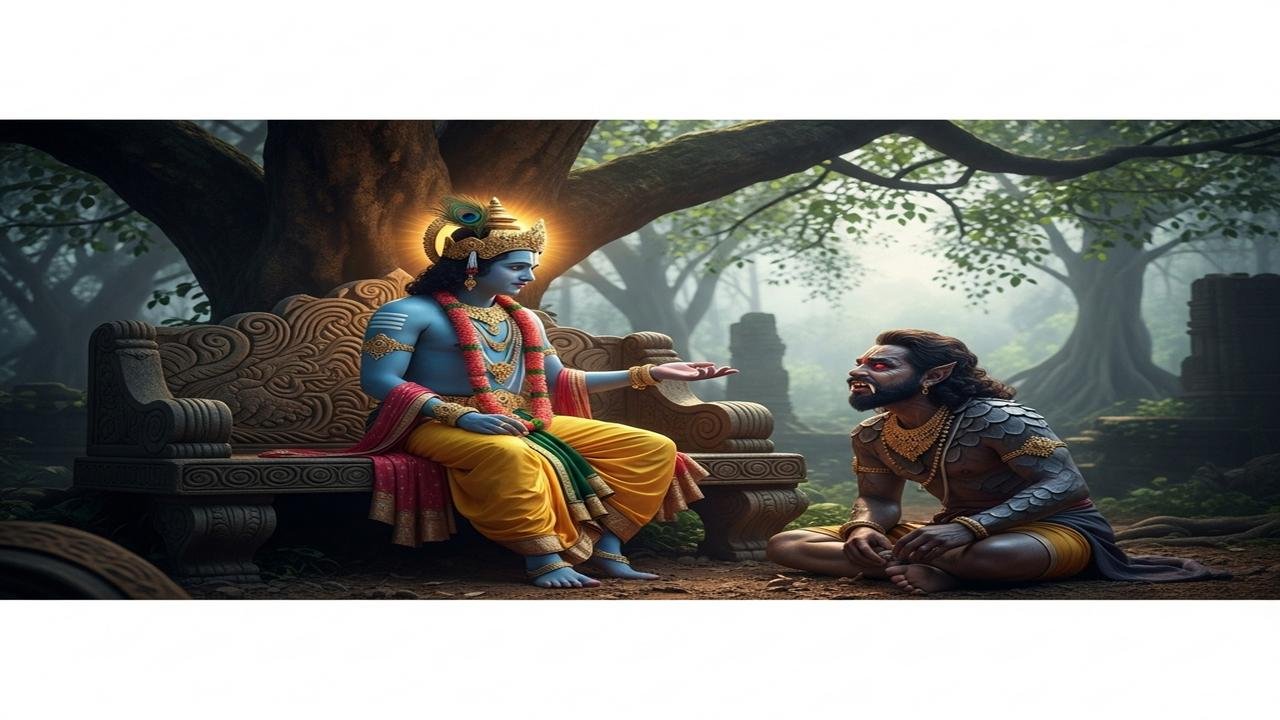

Krishna Explains the Fate of the Demonic

What Krishna says about the “demonic”

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna addresses human nature as a spectrum of qualities. In chapter 16, commonly titled Daivasura-sampad-vibhaga-yoga (the distinction between divine and demonic qualities), he lays out two clusters: the daivi sampat — divine qualities (fearlessness, purity, compassion, steadiness), and the asuri sampat — demonic qualities (hypocrisy, pride, cruelty, ignorance). Krishna is not only diagnosing behaviour; he also describes the consequences of these dispositions and points to means of change.

How the Gita frames the fate of the demonic

Krishna warns that those who cultivate demonic qualities move away from freedom. The Gita states that such people are bound by their urges, become hostile to truth and community, and are driven into suffering. The text uses strong language: those dominated by asuri traits are said to sink into a fearful, ignoble existence and, ultimately, to pass into lower states of being (often described as hellish worlds in classical commentaries).

Different readers and traditions interpret these consequences at several levels:

- Literal cosmological reading: classical exegetes sometimes accept the Gita’s statements about descent into lower lokas (worlds) or hells as a real consequence in the afterlife for continuing in such ways.

- Psychological-symbolic reading: many modern interpreters read the “hell” as inner suffering — a life of alienation, repeated harmful patterns, and loss of clarity and relationship.

- Theological readings: Vaiṣṇava commentators often stress divine grace — while demonic tendencies bind, sincere turning to God can overturn even grave past actions; Smarta and Shaiva readings may emphasise moral purification and knowledge.

Which traits are called “demonic”?

Chapter 16 lists specific traits that form the asuri cluster. Paraphrased, these include:

- Hypocrisy and arrogance

- Ignorance of one’s true self and of dharma (ethical duty)

- Cruelty, harsh speech, and lack of compassion

- Possessiveness, deceit, and self-centeredness

- Obstinacy, hatred of the wise, and inclination to create disorder

These are not merely moral failings; in the Gita’s worldview they are binding forces that condition future choices and, cumulatively, lead away from liberation.

Consequences Krishna describes

- Loss of inner freedom: the demonic nature reinforces craving, fear, and compulsive behaviour, narrowing choice.

- Social harm: such qualities disturb families and communities, provoking violence and discord.

- Rebirth in lower states: traditional readings take Krishna’s language to mean deterioration in the cycle of birth and death — emergence in less favorable circumstances or suffering realms.

- Final spiritual consequence: the Gita contrasts this with the fate of those who cultivate divine qualities, who attain peace, auspicious birth, and ultimately liberation or union with the divine, depending on the commentator.

How different schools understand the warning

- Advaita Vedanta (Shankara and followers): emphasizes ignorance (avidya) as the root. The fate of the demonic is seen as further entanglement in samsara; liberation requires knowledge and discrimination.

- Visishtadvaita (Ramanuja): stresses both moral conduct and surrender to God. Demonic tendencies are serious but can be overcome by bhakti and divine grace.

- Madhva and other dualist traditions: often read the distinctions morally and ontologically; persistent asuri behavior is a grave obstacle to attaining the auspicious worlds or closeness to God.

- Bhakti and Puranic outlooks: the Bhagavata Purana and other texts show that even deeply flawed persons can be transformed by sincere devotion; past sins do not irrevocably bar one from grace.

Remedies Krishna prescribes

Krishna does not leave the reader in despair. He prescribes concrete alternatives and practices that can reverse demonic tendencies:

- Cultivate daivi qualities: fearlessness, self-control, purity, steadfastness in study and worship, compassion and nonviolence (Gita 16:1–3).

- Right action: perform one’s duty without attachment to results (karma-yoga), which weakens selfish patterns.

- Sattvic transformation: working to increase sattva (clarity) over rajas (activity) and tamas (inertia) through disciplined life, ethical behaviour, study, and meditation.

- Devotion and surrender: Gita 18:66 and many Puranic passages point to turning to God (bhakti) or a spiritual teacher as a powerful remedy.

- Self-knowledge: inquiry into the self and removal of ignorance (avidya) as taught in Jnana traditions.

Stories and lived traditions

Across the Mahabharata and the Puranas, Krishna’s role often includes confronting and destroying literal demons — Kamsa, Putana, and many others — who represent social and spiritual disorder. In devotional practice these episodes are used both as historical-religious memory and as symbolic teaching: the inner enemies — pride, greed, hatred — must be recognised and removed.

In temples, festivals, and Kathas, priests and storytellers emphasise different aspects: moral warning, divine justice, or the compassionate possibility of redemption. That variety reflects the plural religious landscape of India, where metaphors, ethics, and theology are woven together.

Practical takeaways

- Krishna’s teaching is both diagnostic and prescriptive: identify harmful tendencies, understand their consequences, and adopt practices that cultivate purity, self-control, and compassion.

- “Demonic” in the Gita is not a permanent label; it describes a set of tendencies that can be changed by discipline, knowledge, and devotion.

- Interpretations vary: some communities focus on the cosmological consequences, others on inner psychological and social harms, and many combine both views.

Note: traditional spiritual practices—fasting, intense breathwork, prolonged silence—can affect health. If you wish to try them, consult a qualified teacher and, where appropriate, a medical professional.

Reading Krishna’s words in chapter 16 offers a stark ethical map: the demonic is not a foreign monster but patterns within us that yield predictable harm. The Gita’s counter-proposal is practical and plural: refine conduct, steady the mind, pursue knowledge, and—across many traditions—turn the heart toward the Divine.